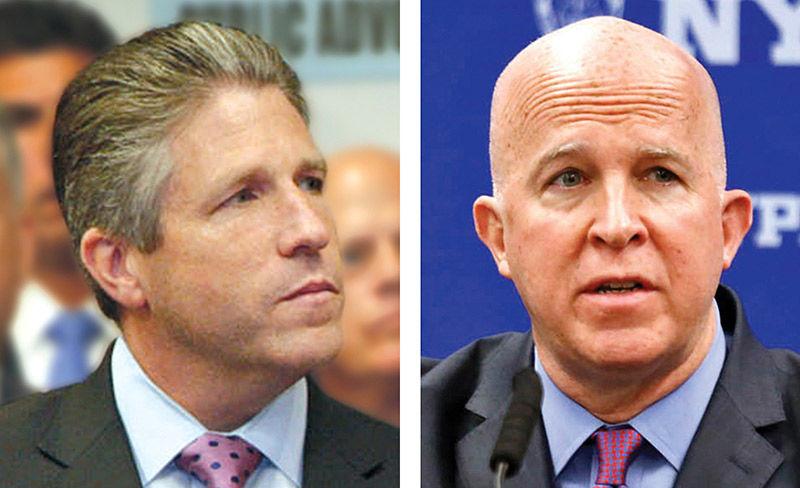

PASSIVE AGGRESSION ON PANTALEO?: While Police Benevolent Association President Pat Lynch (left) sounded more like a labor bureaucrat than the leader of a union representing people whose jobs carry risks, his warning that his members would refrain from engaging in possible use-of-force situations unless supervisors and Emergency Services Unit personnel were on hand put pressure on Police Commissioner James O’Neill (right) that may partly offset what he is feeling from Mayor de Blasio’s pledge of ‘justice for the Garner family’ in deciding whether to fire Daniel Pantaleo.

PASSIVE AGGRESSION ON PANTALEO?: While Police Benevolent Association President Pat Lynch (left) sounded more like a labor bureaucrat than the leader of a union representing people whose jobs carry risks, his warning that his members would refrain from engaging in possible use-of-force situations unless supervisors and Emergency Services Unit personnel were on hand put pressure on Police Commissioner James O’Neill (right) that may partly offset what he is feeling from Mayor de Blasio’s pledge of ‘justice for the Garner family’ in deciding whether to fire Daniel Pantaleo.

Early on July 29, working a midnight-to-8 a.m. shift, Sanitation Worker Tim Moore took a routine ride from his Brooklyn garage across the Verrazzano Bridge, bound for a dump site in Staten Island, when he spotted a woman who seemed agitated walking near a car that had stopped midway on the bridge.

She had nothing to do with his job, which at that moment involved transporting and then unloading collections from recycling. But Mr. Moore pulled over his truck, got out, and approached the woman while telling her, “Don’t do anything crazy.”

She ignored him and headed toward the short steel barrier as if she planned to leap from the bridge into the Narrows below, but he followed and grabbed her to prevent it. She responded by swinging her backpack at him and repeating, “I got the right to do this,” he told this newspaper’s Richard Khavkine in a phone interview two days later.

Mr. Moore held onto her until a police car arrived, and the cops took the woman away. Reflecting on the incident a bit more than 48 hours later, he told Mr. Khavkine, “It’s uncomfortable, walking the Verrazzano that time of night.” Without waiting to be asked why he had done it, then, he explained, “In good faith, I couldn’t drive past and not do anything. If I would have found out that that woman jumped and I didn’t do anything, shame on me.”

An Angry Contrast From PBA Leader

His words resonated two days later, when Police Benevolent Association President Pat Lynch angrily reacted to a recommendation by NYPD Deputy Commissioner of Trials Rosemarie Maldonado that Police Officer Daniel Pantaleo should be fired for acting recklessly five years earlier by applying a department-banned chokehold during the struggle that was a contributing factor in Eric Garner’s death.

During a press conference at the union’s headquarters, Mr. Lynch called it a “horrible decision” that would have a chilling effect on cops confronted by the prospect of having to use physical force to make an arrest.

He said he would tell his members that “when someone calls 911 and dispatchers call you and there’s a circumstance where you have to put your hands on someone, call your Sergeant first, call Emergency Services second, because you will not have the backing of the city. You will not have the backing of the department…So our police officers unfortunately are in a position of having to protect themselves, rather than spending the time protecting you.”

It was an emotional moment for the PBA president, and he was no doubt expressing the concerns of some, if not most, of his members. But it stood in such sharp contrast to what Mr. Moore had said two days earlier in explaining why he got out of his truck to try to prevent a woman from committing suicide despite the physical risks to himself and even the possibility that he could be sued—”In good faith I couldn’t drive past and not do anything”—that Mr. Lynch came off like a bureaucrat rather than the head of the largest union in a department that bills itself as “New York’s Finest.”

There are large elements of risk that go with being a police officer, however much cops may disregard them during the routine parts of their days on patrol, and sometimes when routine turns to chaotic, life-and-death situations. It is why training is more important for first-responders than it is for many civilian jobs—it gives them a foundation from which to make well-reasoned decisions when there is no time for lengthy deliberation or consultation with supervisors who are not at the scene.

Officer Pantaleo was one of a group of cops responding to orders from above—reportedly by then-Chief of Department Philip Banks III—to make arrests of those selling loose cigarettes along a strip in the Tompkinsville section of Staten Island on July 17, 2014. Mr. Lynch pronounced “loosies” as if fully aware of how ludicrous the order sounded—and probably did to many ears even before a man died because of how it was executed—when a department where more rational heads were making the decisions would have concluded it was a civil matter best left to the city Department of Consumer Affairs.

Even amid then-Police Commissioner Bill Bratton’s emphasis on quality-of-life policing, he couldn’t make a public-safety case for arresting the purveyors of untaxed cigarettes the way he could for pursuing turnstile jumpers because of past cases in which those committing that offense were discovered to have been carrying guns. Turnstile-jumpers are not among the deep thinkers of the criminal trade, but that action has them in rapid motion that might allow them to evade capture long enough to ditch the gun before being apprehended.

A man selling loosies, on the other hand, would be a more-stationary target, meaning he’d have to be a complete idiot to be packing. That would be doubly true for someone like Mr. Garner, who weighed in at nearly 400 pounds, making flight a non-option if confronted by the law.

Petty Crime, Major Force

The pettiness of his criminal activity was one of the reasons the outrage was so great over a death that, if not primarily caused by the chokehold, had been set in motion by that initial violent encounter with Officer Pantaleo. Mr. Garner was then forced to the ground and had his chest sat on by another cop while Mr. Pantaleo was grinding his face into the pavement. For anyone, that would have been severe physical trauma; for someone who was severely obese, had a heart condition and was asthmatic, it proved fatal.

Mr. Pantaleo’s able and tough-minded attorney, Stuart London, tried to make the case that Mr. Garner was a victim of those pre-existing conditions and his poor judgment in turning the encounter into a taxing struggle rather than submitting to arrest. But the dead man’s life choices up to then were testament to his often not making good decisions.

That didn’t justify Officer Pantaleo’s decision to react to Mr. Garner’s brushing off his hand when he tried to handcuff him by moving first to a seat-belt hold and then, when his antagonist proved too wide to bring under control that way, the department-banned chokehold.

Ms. Maldonado gave the officer a pass on moving to escalate the confrontation to make the arrest rather than allowing Mr. Garner to continue his argument with Mr. Pantaleo’s partner, Justin Damico. In finding him reckless—in a report that has not been released to anyone other than Mr. London and the Civilian Complaint Review Board—she seemed to be saying that this was not one of those cases in which a cop could justifiably ignore the NYPD’s ban on chokeholds because using one was the best way for him to avoid serious physical injury.

The U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District, Richard Donoghue, last month cited as one justification for Officer Pantaleo deploying that hold his concern that they had moved perilously close to a store window and he needed to act to prevent both of them from crashing through it. But the cell-phone video shot by Ramsey Orta, a friend of Mr. Garner’s, seemed to indicate that this became a possibility only after Officer Pantaleo yanked Mr. Garner’s neck backward and the bigger man’s sheer weight propelled them toward the storefront.

‘A Police Slowdown’

Mr. Lynch’s advice to his members not to use force without first speaking to their Sergeants and then summoning the NYPD’s Emergency Services Unit before acting led NY1 “Inside City Hall” host Errol Louis—the son of a retired NYPD Captain—to assert during an Aug. 5 interview of Mayor de Blasio, “It sounded like essentially the equivalent of a kind of a police slowdown, to sort of work to the exact strictures of both the contract and the patrol book without using the discretion that every patrolman in fact has.”

Mr. de Blasio said nothing like what he called an illegal job action had occurred yet, and said that when one took shape in early 2015 following the assassination late in 2014 of two Police Officers in Brooklyn for which some cops held the Mayor responsible, “the people of this city did not take well to it. It makes no sense in the world for a union official to tell officers not to do their job.”

But a young officer I spoke to the following afternoon said cops, without being instructed to by their union, were ready to “slow things down—not in a job action tying up everything. But make sure a supervisor is there, and do things according to the Patrol Guide,” in the wake of the recommendation that Officer Pantaleo be fired.

Asked about Mr. Lynch’s warning that if Commissioner O’Neill followed through on Ms. Maldonado’s recommendation, he would “lose the department,” this officer—call him Steve—replied, “If he fires Pantaleo, the department’s gonna turn on him, and if he doesn’t, he’ll have to resign,” based on remarks the Mayor has made about his desire to bring “justice to the Garner family.”

Asked why he and his fellow officers viewed the case as a litmus test for the Commissioner, given that much of the public seems to believe firing Officer Pantaleo would be appropriate given his use of a department-banned chokehold and its role in Mr. Garner’s death, Steve said, “The Police Department grapevine is based on bad information, but what I’m hearing is that what he might get fired for is reckless endangerment. What everybody is thinking is, it wasn’t really a chokehold” based on the Patrol Guide definition.

‘Gray-Area’ Concerns

While that’s at odds with public perception of the hold, he continued, cops he knows consider Mr. Pantaleo’s wrapping his arm around Mr. Garner’s neck “a movement that is in a gray area. Cops are afraid if they get into a gray-area incident, they could get fired.”

One reason public reaction about the incident has been so strong was the lack of urgency displayed by Officer Pantaleo’s fellow cops once Mr. Garner had been subdued and lay unconscious on the pavement. Not only did none of them attempt to perform CPR, when an ambulance finally arrived, they seemed by their body language to be discouraging swift action by the EMTs rather than alerting them that the situation might be dire. And during Mr. Pantaleo’s departmental trial, that impression was reinforced by introduction into evidence of a text message from a Lieutenant overseeing the operation responded to a subordinate’s concern that Mr. Garner would die that this was “not a big deal.”

“A death in custody is always a big deal,” Steve said. “If someone commits suicide in custody or has a heart attack, it’s a big deal.”

But, he added, “Perps will try to play you. I think [the cops at the Garner scene] were in the belief that he was in some kind of distress but they weren’t sure. And with [cell-phone] cameras all over the place, somebody might decide to put on a show, make it seem worse than it is.”

Given Mr. Garner’s obesity, I asked, wouldn’t it have made more sense to err on the side of caution and assume he was in serious need of medical help?

“You can get in the position where cops get very blasé” because of what they encounter on patrol, Steve replied. He then added, “If you look at the big picture, that happened in 2014. This is a completely different job now,” partly because of changes that were made in both training and equipment as a reaction to the Garner incident.

“We didn’t have Tasers then, we didn’t have body cameras,” he said of himself and fellow patrol officers. “And the Police Department then was still in that aggressive, proactive mind-set.”

Eased-Up Enforcement

Because of the fallout over an incident that grew out of the sale of loosies combined with the heavy emphasis on building relationships between neighborhood cops and the communities they patrol, he said of his superiors, “They’ve lost interest in that quality-of-life type of issue. Since the Garner case, if you’re caught with an open container, at this point it’s an OATH summons,” a citation dealt with by the city’s Office of Administration Trials and Hearings, “where it’s essentially civil court. If you have three summonses for urinating in public or riding a bike in the park after dark, then you’ll get a criminal summons.”

Steve continued, “Marijuana, they really don’t want you arresting for that unless you have a warrant [outstanding for the suspect] or there’s some kind of other problem.”

Asked about the mood in the field, he said, “Morale is, I would say, at a pretty low point, certainly among the guys on patrol. Cops are usually disgruntled, but they’re a little more disgruntled than usual. The general feeling is [Officer Pantaleo] didn’t do anything outside the parameters of the job—it just unfortunately turned into a tragedy.”

Steve acknowledged that the mood of the city as a whole could get considerably worse if Mr. O’Neill opted not to follow Deputy Commissioner Maldonado’s recommendation. “If [Mr. Pantaleo] keeps his job, there are gonna be massive protests, and it’s the middle of the summer—there’s some concern there could be riots,” he said.

Speaking about the officer having kept his arm wrapped around Mr. Garner’s neck all the way to the ground and then mashing his face into the pavement, he continued, “Once Garner started to pull forward and they started to fall, there was some feeling that he should have re-positioned himself, moved his arm off his neck and gotten him on the ground and handcuffed him.”

But on the other hand, Steve said of Mr. Garner, “They might have pepper-sprayed him and he’d have wound up having an asthma attack,” possibly with a similar end result.

No such ambivalence was expressed by Gene O’Donnell, an ex-cop and former prosecutor who is a Professor of Law and Police Studies at John Jay College of Criminal Justice. “In the Garner case, he was punished for a bad outcome,” he said of Officer Pantaleo during an Aug. 8 phone interview.

Obeying Cops is ‘Major’

“When the police tell someone to cooperate, our whole system is predicated on people agreeing to do that,” he said. “It’s the majesty of the uniform and the power that’s instilled in the office. That’s not a minor thing—it’s a major thing.”

Mr. O’Donnell contended that the department’s response to the incident “went off the rails” from the time that then-Commissioner Bratton “knowingly and recklessly endorsed the idea that this was a chokehold,” even though Mr. Pantaleo’s hold was nothing like the ones that created such problems for Los Angeles cops when he was Chief of Police there.

“The Garner case has become a fable in many ways,” he said. “It exacerbates the pain [for the dead man’s family] to go into great detail, but you have to go into great detail to refute the story that has grown out of this.”

Shortly after Mr. Garner’s death, Professor O’Donnell, who said then that he believed Mr. Pantaleo was “salvageable” as a cop, argued that the incident had been tainted from the time that the order came down to make arrests, contending that selling loosies was a civil offense that should have been handed off to city Consumer Affairs officials.

Speaking now, he said, “You have a bungled arrest, you have a junk arrest—a guy lost his life because of cigarettes. A person died, but there is no evidence that the cop tried to kill him.”

And, he contended, “The day this happened is the end of hands-on policing. And this case has had a national impact, with other cities changing their policing because of it. You can’t look at Pantaleo without looking at Brownsville and the water attacks on the cops” in mid-July. “If those cops had turned around and confronted” their assailant, whom Mr. O’Donnell said was subsequently discovered to be a gang member, “that would’ve been a very violent encounter. That is gonna be one ugly video if you’re doing your job properly.

“A chokehold looks bad even without the outcome,” he explained. “With the police engaged in the adversarial work they do, the force has to be emphatic.”

What Mr. Lynch’s remarks signified, Mr. O’Donnell said, was that “in the minds of the cops, that’s off the table. That’s what O’Neill wants—he doesn’t want them to be involved. And the PBA has endorsed that—that it’s just too risky to use force at this point.”

Won’t Shy From Some Cases

He was less certain that Mr. O’Neill would lose the confidence of his troops if he fired Officer Pantaleo. Even with the aversion to use force that has developed, Professor O’Donnell said, “Police are going to be directed to go to scenes like domestic violence calls and they’re going to have to arrest the offender,” and they’ll be sure to have supervisors present for those confrontations.

“But you’re definitely in uncharted territory,” he continued. “There are a lot of collateral consequences to the Garner case.”

He then turned his attention to Mr. de Blasio, who he said with his remarks about the case during the July 31 Democratic presidential debate had set “a terrible precedent [by making] it an ideological conversation. He acts like he’s still the Public Advocate, up on a flatbed truck. A Mayor has to lead on public safety. He has to say we have a damaged system, but it’s the only one we have and we have to fix it.”

Mr. O’Donnell added, “To take this event and put it on the shoulders of patrolmen is an evil thing to do.”

Arnie Kriss, who during Mayor Ed Koch’s first term held the job now occupied by Ms. Maldonado, said, “It is incumbent upon the Police Commissioner, in this case O’Neill, to reach his decision regardless of any pressure from the Mayor.”

Not There to Be Popular

And while the PBA has been even less subtle than the Mayor about what its members believe is the right decision, Mr. Kriss said if Mr. O’Neill’s verdict “means that the rank and file is angry with him, that’s part of being a leader.”

At the same time, he noted the unique circumstances of this use-of-force case, in which Mr. Pantaleo deployed what would be regarded by the average New Yorker as a chokehold—notwithstanding how it may be defined in the Patrol Guide—and a man ended up dead at the end of the struggle. And the huge amount of attention this case has gotten means this is one in which public opinion carries more weight than a rulebook definition of what a chokehold is.

“The cops should not be fearful based on what O’Neill does in this case,” Mr. Kriss said. “If they do their job right, they should not be punished or lose their job.”